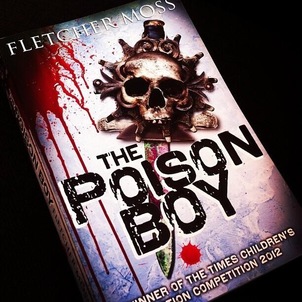

The Poison Boy

Winner of The Times/Chicken House Children's Fiction Competition, 2012

Once, I went by a different name. The name of a park in Manchester. Which was in turn the name of a Victorian Alderman of Manchester, Fletcher Moss. Having swiped the pseudonym, I wrote The Poison Boy, which won The Times/Chicken House Children's Fiction competition in 2012 and somehow managed to get shortlisted for Staffordshire Young Teen Fiction Award, the North East Book Award, the Leeds Book Award, the Calderdale Children's Book of the Year, the Kent Themed Book Award and the prestigious Branford Boase Award, without winning any of them.

Sleepwell and Fly

...was the name of my old blog. You'll remember it well. Three years, 80 posts, single-figure readership. Here's some of the older stuff you might enjoy. Three posts that provide a tasty little sample of what you were missing.

The Stranger in the Room

I once dedicated a lot of time – more than was sensible or healthy for a grown man – building an imaginary city called Highlions. I visited it almost every night for years, walking up and down its streets, constructing it as I went; dropping a great island into the middle of a river here, putting up a theatre there, adding a district up by the church, clearing sections, repopulating them, adding wells and squares, stitching in lawns and gardens and a street of fountains. In the end, I knew it really well. I could tell which neighbourhood I was in by the sound of the river or the quality of the street slang.

Then I learnt something. It’s one thing building the world – it’s quite another introducing it to a reader. With this big sandbox of tricks at the ready, the temptation is to throw your traveller right into the middle of it; start with a riot of sights, sounds, smells; open chapter one on the busiest street during a coronation, for example - parades, crowds, sweat and bustle – a firework display of bold and brilliant world building.

Here’s the thing. I couldn’t get it to work. It was too much crazy in far too big a helping; overwhelming for anyone who read it. They’d say, “What’s this?” or “Why’s this happening? What does this word mean? Who’s this guy?”

So I started scaling back. Maybe not the parade, I thought. Let’s start with market day. It still sucked. Oooh Kay. Maybe a quiet street…

Eventually I ended up with a room. And then it suddenly started making sense. One boy wakes in a room with no recollection of how he got there. Now I could build slowly. Corridor, balcony, roof, cellar, each contributing to our growing sense of the world in which the action operates. In the finished version of the book, the first hustle-and-bustle street scene takes place in Chapter Six. The scene I once tried opening with is now Chapter Thirty One.

It was long after I’d gone through this torturous process that I saw others had tried and failed where I had. Chris Wooding, discussing the troubles he endured whilst writing his novel The Fade, comments; “I only cracked it when I rewrote it so Orna starts the book in prison. That way, I got to show the reader a tiny space in the world, and gradually expand it through flashback.” As soon as I saw Wooding – a damn fine writer – confess to having to start small, I was suddenly struck by what I’ve called here the ‘stranger in the room’ device. I swear I’d never noticed it before, rookie idiot that I am.

And as is often the way with these things, once you see it once, it’s suddenly everywhere: if you’re a gamer, the room in question is often a prison cell – three epic fantasy games from The Elder Scrolls series, Morrowind, Oblivion and Skyrim, all open with imprisoned characters before gradually introducing a new and unfamiliar world. So does Dishonored. Emma Pass does it beautifully in her wonderful dystopian debut Acid, and James Dashner, not to be outdone in the claustrophobia stakes, opens The Maze Runner in a lift. Atwood does it in The Handmaid’s Tale; Treasure Island does it; The Hobbit does it; The Count of Monte Cristo does it twice.

Makes me wonder how I never noticed, really.

So let’s imagine you’re a writer wanting to set a novel in a thrilling and original fantasy world. Not one that reshuffles a pack a familiar tropes; one that astonishes and delights with its freshness. One that lives and breathes and when struck with a tuning fork rings clear and true.

Go for it, brave writer. But start off with a stranger in a room, OK?

Thirty Minutes with John Le Carre

I’m attempting to transform myself into a proper novelist one podcast at a time.

The particular downloads I’m talking about here are episodes of Radio 4’s Book Club which has free archives readily available. It’s basically James Naughtie and guest scribbler exploring the writing process, characterisation, themes, influences and inspirations for the chosen novel, followed by some reader observations and questions. It’s always a great listen particularly, for some reason, when the guest in question is a crime or espionage thriller writer. PD James was wise and insightful, Ruth Rendell was fascinating, Elmore Leonard was frank and funny.

Then I listened to John Le Carre discussing his famous Smiley trilogy. Before I go on, I’ll level with you here, folks – I’ve never read of word of Le Carre. Radio adaptations and movies, yes – prose; not a damn syllable. Castigate me now, I fully deserve your scorn, etcetera. The man was brilliant. Perhaps it was partly because his audience were drawn from students from the Falmouth School of Creative Writing as well as fans and regular readers, but Le Carre was in calm, clear and quietly inspirational advice-giving form, and as he talked I realised he was demonstrating without any fuss or fanfare the qualities that make great writers.

Here, in distilled form, was what struck me:

Determination

“Those first three books” says le Carre breezily, “were written while still in harness.” Aside from being a lovely phrase, this was arresting for other reasons. Three novels planned and written whilst holding down a hugely stressful job as a member of the secret service? Wow. That dwarfs my struggles just a tad – yours too, I’ll bet. Guess I need to man up a bit.

Courage

Describing the trilogy Le Carre says, “It grew out of a great sense of failure I had. After writing a book which was widely regarded as awful, called ‘The Naïve and Sentimental Lover’, I lost a lot of confidence and felt very hurt.” Then here’s the killer line. The Le Carre response to setback: “I threw my lance into the middle of the enemy and thought I would fight it out. I’d plan a trilogy.” Superb, eh? I hope I have half his courage when Poison Boy bombs.

Fortitude

“I flailed around writing material for a full year,” Le Carre admits of one novel. “Then one day I took it up to The Beacon and set fire to the whole damn lot.” The crowd laugh appreciatively as he says this. But under that admission sits a strength of character that’s pretty awesome. Duly noted.

Clarity

When asked how he plans books, Le Carre speaks with the kind of clarity of purpose only an expert can. “It’s childhood images to begin with,” he starts. “Then I want one character who can take the reader by the hand – one the reader can trust. Then I want terrain. Locations become characters. Then I want conflict. What do they want of this man? What demands are going to be made of him? These things are important for setting up a story.”

It was a masterclass of calm and good-humoured understatement, and it’s just sitting there waiting to be downloaded for free. That’s the thing with this great technological renaissance we’re living through: at its best, it’s about the democratisation of education – about universities in the UK and the states putting their lectures online for free; about John Le Carre and hundreds of others sharing the secrets of their creative processes for nothing but the cost of an internet connection.

So thanks, John.

All I need now is a copy of ‘Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy’ to add to my teetering TBR pile, and sufficient grit and gumption to be more like the man himself. The bar’s been set pretty high, I think you’ll agree…

Water and Ice

There’s this thing about writing and liquid – people talk about the writing process like we’ve each got some sort of creative plumbing system, and it’s either running smoothly or mis-firing. When things are going well, we say the words ‘flow’, as if all our valves and chambers are flooding beautifully, and when the process slows or stops, we say the words have ‘dried up’ or worse still, that we’re ‘blocked’.

I guess one of the reasons I don’t ever worry about or experience ‘writer’s block’ is because I don’t particularly subscribe to this metaphor of flow or block in the first place. This isn’t an act of will on my part; even on a subconscious level I don’t ever consider the creative process in terms of water.

Unless it’s frozen water, that is.

I was struck recently by American sitcom writer and comedian Amy Poehler’s much more revealing comparison that writing is like hacking ice from the inside of a fridge with a screwdriver. Now this is way more my line of thinking. Poehler’s image emphasises hard work over ease; dogged persistence ‘chipping away’ over effortless ‘flow’.

So my advice in short? Don’t believe in writer’s block, and suddenly, it doesn’t exist.

Instead, writing becomes a process that requires effort and optimism. Sit down at your desk with a song in your heart, friends. And as you spend a few moments contemplating the task ahead of you, try the following:

The Stranger in the Room

I once dedicated a lot of time – more than was sensible or healthy for a grown man – building an imaginary city called Highlions. I visited it almost every night for years, walking up and down its streets, constructing it as I went; dropping a great island into the middle of a river here, putting up a theatre there, adding a district up by the church, clearing sections, repopulating them, adding wells and squares, stitching in lawns and gardens and a street of fountains. In the end, I knew it really well. I could tell which neighbourhood I was in by the sound of the river or the quality of the street slang.

Then I learnt something. It’s one thing building the world – it’s quite another introducing it to a reader. With this big sandbox of tricks at the ready, the temptation is to throw your traveller right into the middle of it; start with a riot of sights, sounds, smells; open chapter one on the busiest street during a coronation, for example - parades, crowds, sweat and bustle – a firework display of bold and brilliant world building.

Here’s the thing. I couldn’t get it to work. It was too much crazy in far too big a helping; overwhelming for anyone who read it. They’d say, “What’s this?” or “Why’s this happening? What does this word mean? Who’s this guy?”

So I started scaling back. Maybe not the parade, I thought. Let’s start with market day. It still sucked. Oooh Kay. Maybe a quiet street…

Eventually I ended up with a room. And then it suddenly started making sense. One boy wakes in a room with no recollection of how he got there. Now I could build slowly. Corridor, balcony, roof, cellar, each contributing to our growing sense of the world in which the action operates. In the finished version of the book, the first hustle-and-bustle street scene takes place in Chapter Six. The scene I once tried opening with is now Chapter Thirty One.

It was long after I’d gone through this torturous process that I saw others had tried and failed where I had. Chris Wooding, discussing the troubles he endured whilst writing his novel The Fade, comments; “I only cracked it when I rewrote it so Orna starts the book in prison. That way, I got to show the reader a tiny space in the world, and gradually expand it through flashback.” As soon as I saw Wooding – a damn fine writer – confess to having to start small, I was suddenly struck by what I’ve called here the ‘stranger in the room’ device. I swear I’d never noticed it before, rookie idiot that I am.

And as is often the way with these things, once you see it once, it’s suddenly everywhere: if you’re a gamer, the room in question is often a prison cell – three epic fantasy games from The Elder Scrolls series, Morrowind, Oblivion and Skyrim, all open with imprisoned characters before gradually introducing a new and unfamiliar world. So does Dishonored. Emma Pass does it beautifully in her wonderful dystopian debut Acid, and James Dashner, not to be outdone in the claustrophobia stakes, opens The Maze Runner in a lift. Atwood does it in The Handmaid’s Tale; Treasure Island does it; The Hobbit does it; The Count of Monte Cristo does it twice.

Makes me wonder how I never noticed, really.

So let’s imagine you’re a writer wanting to set a novel in a thrilling and original fantasy world. Not one that reshuffles a pack a familiar tropes; one that astonishes and delights with its freshness. One that lives and breathes and when struck with a tuning fork rings clear and true.

Go for it, brave writer. But start off with a stranger in a room, OK?

Thirty Minutes with John Le Carre

I’m attempting to transform myself into a proper novelist one podcast at a time.

The particular downloads I’m talking about here are episodes of Radio 4’s Book Club which has free archives readily available. It’s basically James Naughtie and guest scribbler exploring the writing process, characterisation, themes, influences and inspirations for the chosen novel, followed by some reader observations and questions. It’s always a great listen particularly, for some reason, when the guest in question is a crime or espionage thriller writer. PD James was wise and insightful, Ruth Rendell was fascinating, Elmore Leonard was frank and funny.

Then I listened to John Le Carre discussing his famous Smiley trilogy. Before I go on, I’ll level with you here, folks – I’ve never read of word of Le Carre. Radio adaptations and movies, yes – prose; not a damn syllable. Castigate me now, I fully deserve your scorn, etcetera. The man was brilliant. Perhaps it was partly because his audience were drawn from students from the Falmouth School of Creative Writing as well as fans and regular readers, but Le Carre was in calm, clear and quietly inspirational advice-giving form, and as he talked I realised he was demonstrating without any fuss or fanfare the qualities that make great writers.

Here, in distilled form, was what struck me:

Determination

“Those first three books” says le Carre breezily, “were written while still in harness.” Aside from being a lovely phrase, this was arresting for other reasons. Three novels planned and written whilst holding down a hugely stressful job as a member of the secret service? Wow. That dwarfs my struggles just a tad – yours too, I’ll bet. Guess I need to man up a bit.

Courage

Describing the trilogy Le Carre says, “It grew out of a great sense of failure I had. After writing a book which was widely regarded as awful, called ‘The Naïve and Sentimental Lover’, I lost a lot of confidence and felt very hurt.” Then here’s the killer line. The Le Carre response to setback: “I threw my lance into the middle of the enemy and thought I would fight it out. I’d plan a trilogy.” Superb, eh? I hope I have half his courage when Poison Boy bombs.

Fortitude

“I flailed around writing material for a full year,” Le Carre admits of one novel. “Then one day I took it up to The Beacon and set fire to the whole damn lot.” The crowd laugh appreciatively as he says this. But under that admission sits a strength of character that’s pretty awesome. Duly noted.

Clarity

When asked how he plans books, Le Carre speaks with the kind of clarity of purpose only an expert can. “It’s childhood images to begin with,” he starts. “Then I want one character who can take the reader by the hand – one the reader can trust. Then I want terrain. Locations become characters. Then I want conflict. What do they want of this man? What demands are going to be made of him? These things are important for setting up a story.”

It was a masterclass of calm and good-humoured understatement, and it’s just sitting there waiting to be downloaded for free. That’s the thing with this great technological renaissance we’re living through: at its best, it’s about the democratisation of education – about universities in the UK and the states putting their lectures online for free; about John Le Carre and hundreds of others sharing the secrets of their creative processes for nothing but the cost of an internet connection.

So thanks, John.

All I need now is a copy of ‘Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy’ to add to my teetering TBR pile, and sufficient grit and gumption to be more like the man himself. The bar’s been set pretty high, I think you’ll agree…

Water and Ice

There’s this thing about writing and liquid – people talk about the writing process like we’ve each got some sort of creative plumbing system, and it’s either running smoothly or mis-firing. When things are going well, we say the words ‘flow’, as if all our valves and chambers are flooding beautifully, and when the process slows or stops, we say the words have ‘dried up’ or worse still, that we’re ‘blocked’.

I guess one of the reasons I don’t ever worry about or experience ‘writer’s block’ is because I don’t particularly subscribe to this metaphor of flow or block in the first place. This isn’t an act of will on my part; even on a subconscious level I don’t ever consider the creative process in terms of water.

Unless it’s frozen water, that is.

I was struck recently by American sitcom writer and comedian Amy Poehler’s much more revealing comparison that writing is like hacking ice from the inside of a fridge with a screwdriver. Now this is way more my line of thinking. Poehler’s image emphasises hard work over ease; dogged persistence ‘chipping away’ over effortless ‘flow’.

So my advice in short? Don’t believe in writer’s block, and suddenly, it doesn’t exist.

Instead, writing becomes a process that requires effort and optimism. Sit down at your desk with a song in your heart, friends. And as you spend a few moments contemplating the task ahead of you, try the following:

- Don’t write in sequence. Save a killer scene for those days when hacking ice feels like it isn’t much fun. Avoid death-by-chronology.

- Jump the problem. Put a long “…………….” for that particularly tough icy outcrop, and carry on as if you’d already dealt with it. (Tip: Don’t then submit your mss having totally forgotten to sort it out. Been there, done that.)

- If you don’t fancy the piece you’re hacking at, switch to a scene with lots of dialogue. Tune-in to everyday talk and write. You chip away at lots that way.

- Use ‘The Ten Minute Rule’. It a psychological trick that goes like this: “This section is really hard and I can’t see how to hack through it. So I’ll write something – any damn thing, without any critical assessment – for just ten minutes. Then I’ll stop.” I’ve done this a whole load of times – and found myself returning to reality half an hour later, the ten-minute curfew totally forgotten, with a bunch of words. Which is a bunch better than nothing. (Tip: This one works even better with headphones on, and playlist cued up.)

- Hack out the final scene of your novel, right now this moment. If you’ve never considered your final scene, this can be fun. If the actual problem is your final scene, sit yourself down and watch the last five minutes of five great movies, then read the last five pages of five great novels, then try the ten-minute rule.

- Write a scene you know will not be in the novel, but will appear in a lavishly-illustrated fully expanded ‘director’s cut’ version of the book that one day will be greeted with rapturous critical acclaim, sell millions and keep you in beer and sandwiches for the rest of your days.

Proudly powered by Weebly