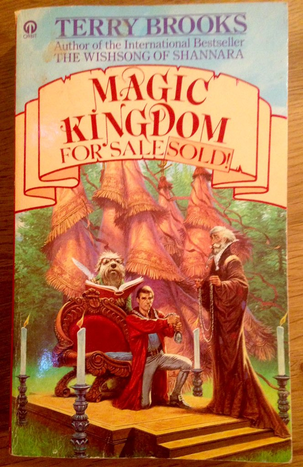

In the final stages of editing Lifers, I was in a regular back-and-forth discussion of the book with the team at Chicken House and they suggested changing some of the character names. There were two in particular they thought needed adjustment, both on the grounds of phonetic similarity; they began with the same letter, or sounded (accidentally) too similar. So my protagonist’s best buddy ended up being called Mace – a move I was pretty pleased with, since I got to name-check my fave old-skool turn-table hip-hop outfit De La Soul – and my female protagonist became Ellwood, something I found harder to take. I loved the name that got discarded. It’ll turn up again in something else, I’m sure. Naming characters is important – as David Lodge will tell you far better than I can in The Art of Fiction. I thought a lot about what to call my protagonist in Lifers before finally settling on Preston. Weird really, because it was a name that made perfect sense in those very early drafts, where one of the ideas I wanted to explore was the shape of urban landscape. Name the kid after a town, I thought. It sorta worked that way for the Wombles… Now, with the book so changed, Preston seems a touch anachronistic but once you’ve lived with a kid for two years and grown fond of them, you can’t contemplate them being called anything else. My daughter, who’s five, has an unerring super-confident fluency in naming fictional characters. Anything that can stand-in for a person, from dolls through magnetised dinosaurs to shampoo bottles, gets named. I’m approximating her pronunciation here, but we’ve had Arto, Bellefusse, (‘belfoose’), Generation Girl, Mosser, Avro, Budi, the Pop-Up Ghost. When she’s playing the role of teacher, she’s the improbably named Mrs Perpatterfew. When I’m asking older kids in creative writing sessions about possible character names, I sometimes get a shrug, and eventually, ‘Bill?’ It puts me in mind of a study of creativity as told by Ken Robinson and animated by the RSA here, which details the findings of a study in which young people were asked to imagine the largest number of possible uses for a paper clip. Draw a line graph of the number of suggested uses plotted against age, and I bet you can guess what it shows. Bill indeed. Here’s to Avri, Budo and the Pop-Up Ghost.  When I was a kid, I loved my fantasy fully immersive. Just a sniff of the real world was enough to put me off a book. I needed to open in a village called something like Irylyn, meet the plucky son of a blacksmith with a single syllable otherworldly name like Nyrt, and set off towards the Mountains of Kirth N’Gah in search of the Dagger of Sagshadoom within, absolute max a chapter or two. Hopefully meeting a fair maid called Unya along the way. This little book changed all that. 1986. I was fourteen. This was Terry Brooks’s first non-Shannara novel, and I leapt on it, only to find it featured a dude called Ben Holiday, and opened in a department store in Chicago. I mean, jeez. Shopping? In America? I was gutted. Then Ben buys a faery kingdom from a catalogue and goes through a magic door to be its new king, and a curious thing happened as I read. I liked it just as much as his other stuff. Maybe, I began to think, the one world works as a foil to the other, and by a process of juxtaposition, we come to critically assess the two states of existence in profound new ways. OK, I didn’t think that. I was fourteen, dammit, I hadn’t even done my GCSEs. But it opened my eyes. Lifers is a magic door story too, and as I invented amazing new ways to screw up the middle of the novel, I realised that one of the big decisions you have to make in a magic door story is this: at what point in the story is your protagonist is going to go through the magic door? Brooks does it on pg 57. That’s 17% of the way through. But a rather more recent inspiration for Lifers was a Stephen King novel called From A Buick 8. Here, the crazy stuff beyond the magic door is glimpsed on pg 447 – 97% of the way through. Hmmm. Two very different models. Having written Lifers as many times as I have, I can conclude only this: a King-style act three journey through the magic door didn’t work for this particular story. And also that a super-early venture didn’t work either. Looking back, it took me a long time to get the positioning right particularly if, as I hoped, the one world would work as a foil to the other, and by a process of juxtaposition, we’d come to critically assess the two states of existence in profound new ways. Or something like that. Here’s a sentence I don’t get to type often: I was having a beer with Melvin Burgess.

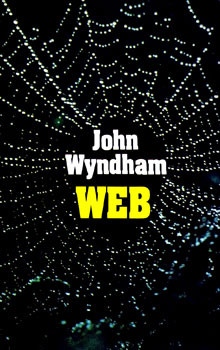

It’s true. One of my heroes. We’d been involved in an event for kids at the excellent Portico Library, and afterwards, in the pub next door, we got to talking about books. Burgess tells this great story about a mutual favourite writer of ours, the sci-fi pioneer John Wyndham. “This is John Wyndham, remember,” Burgess says as he begins. I’ve edited out the colourful language. “John Wyndham. Writer of Day of the Triffids. The Midwich Cuckoos. Apparently, between books, he’d always try and pitch this great, elusive idea to his publishers. The next book was going to be it. I’ve got two words for you, gentlemen, Wyndham would say.” Here, Burgess, does a perfect impression of a writer fuelled-up on the fever-potential of a new idea. “Two words for you. (pause) Killer. Spiders.” And the response, the story goes, would be a kind of embarrassed silence. Yeah great, John. Sounds good. Anything else you’re working on right now? And downcast, Wyndham would shrug and say with a sigh, Well, I’ve got this thing called The Chrysalids… We roared with laughter together at this story - both guessing it was semi-apocryphal. We imagined Shakespeare doing the same. Approaching the money-makers and gate-keepers of Elizabethan theatre at The Globe with this: “I’ve got three words for you, Gentlemen: Codpieces. From. Hell.” Then, excited by this idea that all writers might carry a story around with them – a story they know is killer, but the world at large remains unconvinced - I told Melvin Burgess about mine. Melvin Burgess, the Jedi-master of YA. I told him, in a slightly drunken, unguarded moment, about Ghost Heist. Looking back, I didn’t pitch it well. It’s a heist story, I said. Except the burglars are ghosts. They’re avenging ghosts. Four dead guys bankrolled by a super-rich kid. To his great credit, Burgess listened. Then he sipped his beer and said, very politely, “I’m not sure what the ‘ghost’ element adds to it.” When I got home, I stuck John Wyndham Killer Spiders into a search engine. And whaddayaknow, Web turned up. It was published posthumously in 1979, ten years after Wyndham’s death. He never did convince anyone to take a chance on it. I read Web recently. It’s not a great success. To be honest, I’m not sure what the killer spiders element adds to it. |

Archives

November 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed